In 1969, Austrian-American author Peter Drucker predicted major social and economic change driven by knowledge. However, it was not until the Nineteen Nineties that scientists, managers, management consultants and political decision-makers announced the introduction of the Knowledge economywhere goods and services depend not only on labor but additionally on competencies, skills and concepts. As knowledge was recognized because the Most worthy organizational and economic resource, the urge to administer it grew.

Management scientists in addition to consultants and managers quickly recognized the best challenge of data management. As long as knowledge was within the heads of people, it was difficult for managers to manage.

This shaped the knowledge management agenda, which relied largely on codifying or otherwise capturing knowledge in a written or storable form, equivalent to a manual or guide, which could then be managed.

For the knowledge manager, the proven fact that “we will know greater than we will say” (because the Hungarian-British polymath Michael Polanyi put it in 1966) shouldn’t be particularly problematic. All that should be derived from the person mind are the overall rules and procedures that enable an individual to do their job.

As Julian E. Orr's book Talking About Machines: An Ethnography of a Modern Job When published in 1996, it provided a vital latest perspective – an employee-centered alternative to the manager-centered view of data that had by then taken hold in scholarship and practice. This was achieved through a two-pronged attack on the core tenets of data management.

First, the limited usefulness of things equivalent to manuals, instructions, guides or procedures in enabling competent motion became clear.

Second, and more fundamentally, it emerged that managers are sometimes too detached from the work they’re doing to know the knowledge required to do a reliable job. Orr documented the experiences of the copier technicians of

What made this attack particularly effective was Orr's own background. His research experience as an anthropologist, his previous Army technician training, and his own employment at Xerox enabled him to explain the work of service technicians intimately and vividly, often within the language the staff themselves use.

The manager's need for control

On its face, the book represented the failure of the manual that Xerox service technicians were purported to use when repairing photocopiers. Some of the prescribed procedures simply didn't work. Those that did solved problems that were so routine for the technicians that there was no need for them to seek the advice of the manual.

Still, the manual had some utility, even when the technicians denied it any credibility. They might be useful when technicians don't know where to start out, but develop into worthless once they understand the condition of the machine they’re facing. The reason for that is that they don’t contain the needed knowledge to get the job done.

Instead, this data circulates informally throughout the engineering community, together with knowledge of which spare parts is likely to be useful, which management also tried to manage through personal inventory limits.

At a fundamental level, Orr's book is about managers' insatiable desire for control, often over every part that’s currently viewed as key to the organization's success. A thirst so primal that, as was the case at Xerox, management may quench it without fully understanding what they’re managing.

The management of the technicians were no less than not aware of any official channels through which they might pass on the knowledge that they had gained on site. Knowledge continued to flow into amongst technicians just because they shared a job and a way of community emerged. Instead of data about photocopier repair, there was within the service manual

Rokas Tenys/Shutterstock

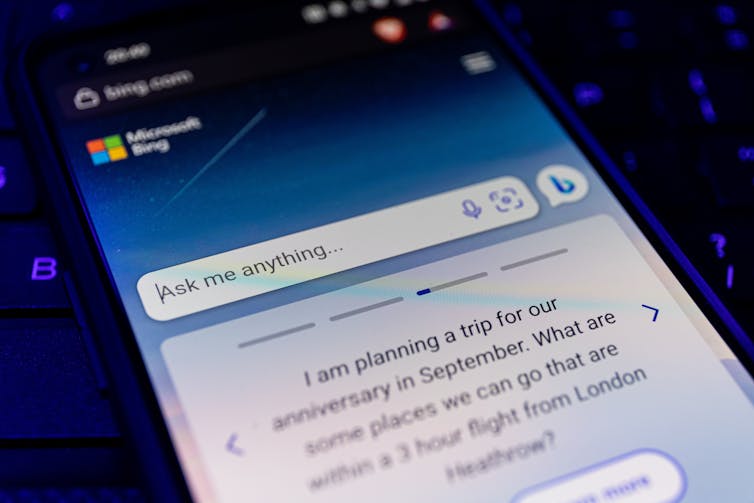

While we must always all the time be wary of management's efforts to create guides and manuals, today we must even be wary of management using artificial intelligence (AI) to exchange and support employees.

As with the Xerox Copier Service Manual, value will depend on how well managers know what’s required to finish a task.

Most people find it difficult to make a transparent distinction between “knowledge” and “intelligence” (unless they ask the AI for a solution).

In principle, it will probably be argued that AI is more knowledgeable. Because it doesn’t share our cognitive limitations, it may very well be immeasurably more knowledgeable than we’re. That's why the associated productivity gains are extremely tempting.

However, our cognitive limitations and the irrational instincts, emotional attachments, and private beliefs to which they cave in give a special flavor to human knowledge.

Like Xerox service technicians, our limitations allow us to perform well in situations where getting the job done relies on creativity, ignorance, or just taking our possibilities, sometimes contrary to established wisdom and customary rules. With this in mind, Orr's cautionary tale – that attempts to administer knowledge might be futile at best or a hindrance at worst – stays as relevant as ever. Sometimes it is best to just allow the knowledge to flow by itself.