If you utilize social media, you almost certainly have encounter deepfakes. These are video or audio clips of politicians, celebrities, or others which are manipulated using artificial intelligence (AI) to make it appear that the person is saying or doing something that they didn’t actually say or do.

If the considered deepfakes scares you, you're not alone. Our current opinion research A study conducted in British Columbia found that deepfakes were at the highest of the list of top AI-related concerns for 90 percent of respondents.

To say that there may be plenty of hype around AI is an understatement. Media reports and commentary from industry leaders concurrently praise AI as “the following big thing” and an existential risk that can wipe out humanity. This sensationalism sometimes distracts from the precise risks we want to fret about, from privacy to job relocation, from energy use to employee exploitation.

While pragmatic political conversations are going down, and never a moment too soon, they’re largely going down behind closed doors.

In Canada, as in lots of other places all over the world, the federal government has repeatedly did not seek the advice of the general public on the regulation of latest technologies, leaving the door open for well-funded industry groups to shape the narrative and plan of action regarding AI design . It doesn't help that Canadian news media keeps quoting the identical tech entrepreneurs. It's like nobody else has anything to say on the topic.

We wanted to search out out what the remaining of society needed to say.

(Comuzi/Better Images from AI), CC BY

Our AI survey

In October 2024 we will probably be on the Center for Dialogue at Simon Fraser University worked with a polling firm to conduct a survey of greater than 1,000 randomly chosen British Columbians to higher understand their views on AI. In particular, we wanted to know their awareness of AI and its perceived impacts, their attitudes towards it, and their views on what we as a society should do about it.

Overall, we found that British Columbians are reasonably knowledgeable about AI. A majority were capable of appropriately discover on a regular basis technologies that use AI based on a standardized list, and 54 percent said that they had personally used an AI system or tool to generate text or media. This suggests that a big portion of the population is sufficiently engaged with the technology to be invited to a conversation about it.

However, familiarity didn’t necessarily translate into confidence, as our study showed that greater than 80 percent of British Columbians report feeling “nervous” about using AI in society. But this nervousness was not linked to catastrophe. In fact, 64 percent said they thought AI was “just one other technology amongst many,” while only 32 percent said it will “fundamentally change society.” 57 percent believed that AI won’t ever truly match the capabilities of humans.

Instead, most respondents' concerns were practical and well-founded. 86 percent feared losing a way of private agency or control if firms and governments used AI to make decisions that impact their lives. Eighty percent thought AI would make people feel more isolated in society, while 70 percent said AI would show prejudice against certain groups of individuals.

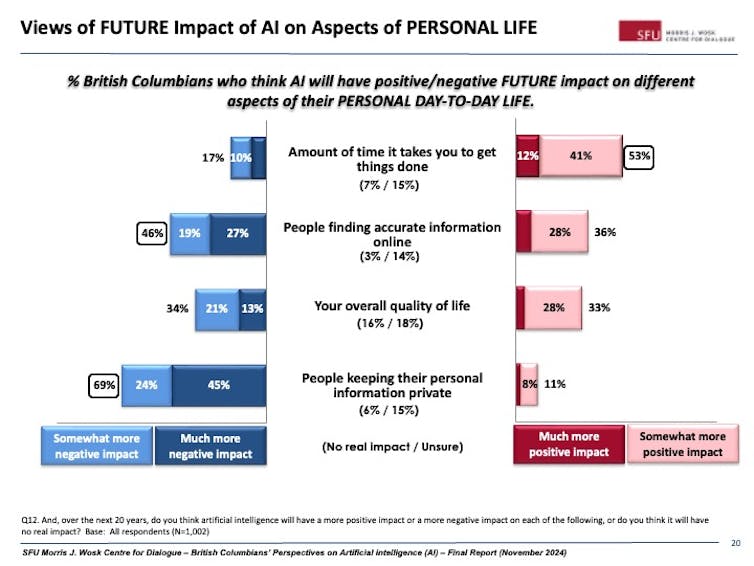

The overwhelming majority (90 percent) were concerned with deepfakes and 85 percent were concerned with using personal information to coach AI. Almost 80 percent expressed concerns about firms replacing employees with AI. When it got here to their personal lives, 69 percent of respondents feared that AI would compromise their privacy and 46 percent feared that they might be unable to search out accurate information online.

(writer stated)

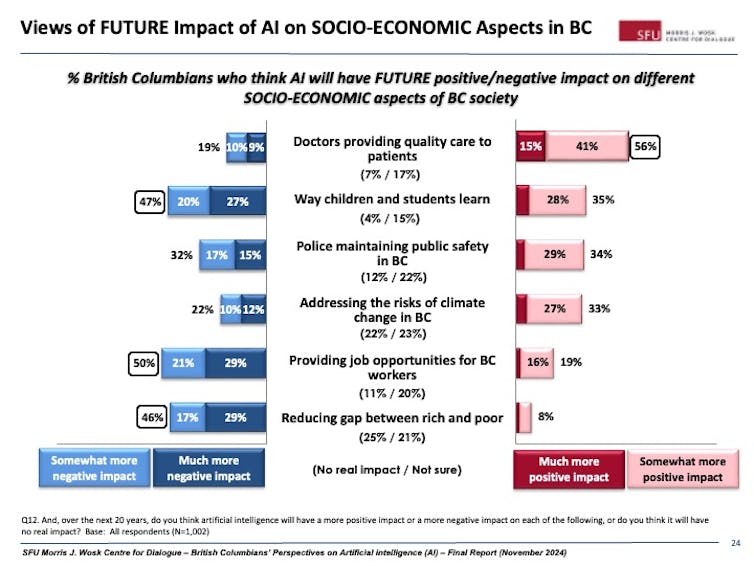

variety of respondents had a positive attitude towards AI. 53 percent were enthusiastic about how AI could push the boundaries of what humans can achieve. Almost 60 percent were fascinated by the concept machines can learn, think or support people in tasks. In their personal lives, 53 percent of respondents viewed AI's potential to get things done faster positively. They were also relatively excited concerning the way forward for AI in certain areas or industries, particularly in medicine, where BC faces a noticeable lack of capability.

If our survey participants had one message for his or her government, it was to begin regulating AI. A majority (58 percent) believed that the risks of an unregulated AI technology sector were greater than the danger that government regulation could hinder the longer term development of AI (15 percent). Around 20 percent were unsure.

(writer stated)

Low trust in government and institutions

Some scientists have argued that the federal government and the AI industry are in a “prisoner’s dilemma” as governments are reluctant to impose regulations for fear of hampering the tech sector. But in the event that they fail to control AI's negative impact on society, they may cost the industry the support of a cautious and conscientious public and ultimately its social license.

Current reports suggest so The adoption of AI technologies in Canadian firms has been extremely slow. Perhaps, as our findings show, Canadians will probably be reluctant to totally embrace AI if its risks will not be managed through regulation.

But here the federal government faces an issue: our institutions have a trust problem.

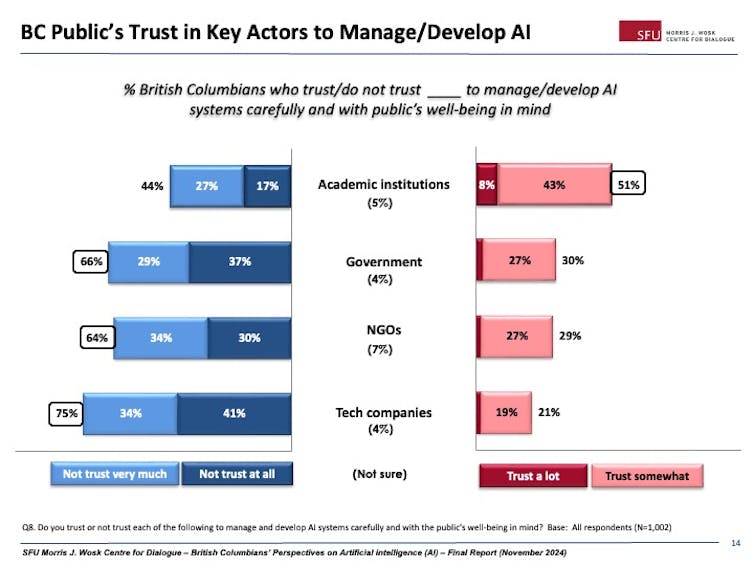

On the one hand, 55 percent of respondents strongly consider that governments needs to be chargeable for setting rules and limiting the risks of AI, slightly than leaving it to technology firms themselves (25 percent), or expecting individuals to develop AI literacy to guard yourself (20 percent).

On the opposite hand, our study shows that trust in the federal government to administer and develop AI fastidiously and with the general public's interests in mind is low, at just 30 percent. Trust is even lower amongst technology firms (21 percent) and non-governmental organizations (29 percent).

Academic institutions perform best in the case of trust: 51 percent of those surveyed somewhat or strongly trust them to handle them responsibly. A bit of greater than half remains to be not exactly a flattering value. But perhaps we just have to see it as a call to motion.

(writer stated)

Towards participatory AI governance

Studies on AI governance in Canada continually indicate the necessity for higher, more transparent and more transparent solutions more democratic mechanisms for public participation. Some would say the subject is simply too technical to ask the general public into, but this portrayal of AI because the domain of only the technical elite is a component of what keeps us from having a really social discussion.

Our survey shows that residents will not be only knowledgeable about and curious about AI, but additionally express a desire to take motion and learn more to assist them proceed to have interaction with the subject.

The public could also be more prepared for the AI discussion than they offer credit for.

Canada needs a federal policy that ensures responsible use of AI. The federal government recently launched one recent AI Safety Institute to higher understand and scientifically address the risks of advanced AI systems. This or an identical body should concentrate on developing mechanisms for more participatory AI governance.

Provinces even have room to take a leadership role inside AI Canada's Constitutional Framework. Ontario and Quebec have done a few of this work, and BC has already done so own guiding principles for responsible use of AI.

Canada and British Columbia have a possibility to advance a highly participatory approach to AI policy. Convening committees resembling our own Center for Dialogue, in addition to many scientists, are completely satisfied to support the discussion. Our study shows that the general public is able to become involved.