There’s a way of pleasure around Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, now open on the Tate Modern, for numerous reasons. First, it’s one in every of the primary major exhibitions to put the present hype surrounding generative artificial intelligence inside a historical context. Second, it addresses the historical amnesia of latest art institutions regarding the mixing of technology in arts practice – something long overdue.

The exhibition revisits a past by which artists dreamed of a future that we are not any longer able to examine. The title is a reminder of the 1984 pop song Together in Electric Dreams by Giorgio Moroder and Philip Oakey. It also evokes Philip K. Dick’s dystopian sci-fi novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), which was concerned with human agency and machine sentience.

This reference gives a way of what’s at stake with the exhibition – the challenge AI poses to traditional notions of artistic practice and creativity. The show brings together artists who’ve collaborated with machines to supply works that challenge human-centred ideas about creativity and sense-making.

By charting the event of optical, kinetic and programmed artistic experimentation, the exhibition gives an insight into the complex interactions of humans and machines as much as the early Nineteen Nineties.

Harold Cohen, AARON #1 Drawing, (1979).

Lucy Green/Tate

The exhibition is organised chronologically into sections and rooms. In the section Dialogues with Machines, visitors encounter Harold Cohen’s AARON. First developed within the late Sixties, it was allegedly the earliest use of AI for making art (depending in your definition of art).

On the wall is Cohen’s large painted canvas, co-created by the artist and machine. Insight into the method is provided by the use of system diagrams and a computer-controlled drawing device displayed in a vitrine. Throughout the exhibition, these sorts of supporting contextual materials emphasise how the assorted automated processes of machines are contingent on human intervention.

Future past

Brion Gysin’s Dreamachine (1959).

Author provided

It’s hard to do justice to the 150 works on show in a brief article. Certain pieces act as signposts to key issues, and the exhibition makes clear how the considering of every artist reflects the time they were working in.

Brion Gysin’s Dreamachine (1959) is a lightweight machine that needs to be checked out together with your eyes closed. It produces a flickering effect that induces a psychedelic experience without using drugs. Dreamachine is a reminder of the ways drugs and technology were once regarded as possible solutions to societal and environmental problems.

The exhibition broadly covers this era of Utopian hope before the commercialisation of the web. It charts a time when computer art was not so closely connected to corporate monopolies of massive tech.

But for all its merits, the choice approaches offered by the exhibition are largely based on a culture of individualism – something further emphasised by bringing these works into the exhibition rooms of the Tate and reinforcing the singularity of the artist. On the one hand, this grants them long overdue visibility; on the opposite (like several museum), it nullifies their political potential by removing social context.

There are exceptions. Samia Halaby’s Land (1988) – a computer-generated kinetic painting which sketches the changing boundaries of the occupied Palestinian territories after 1948 – takes on recent currency given current events.

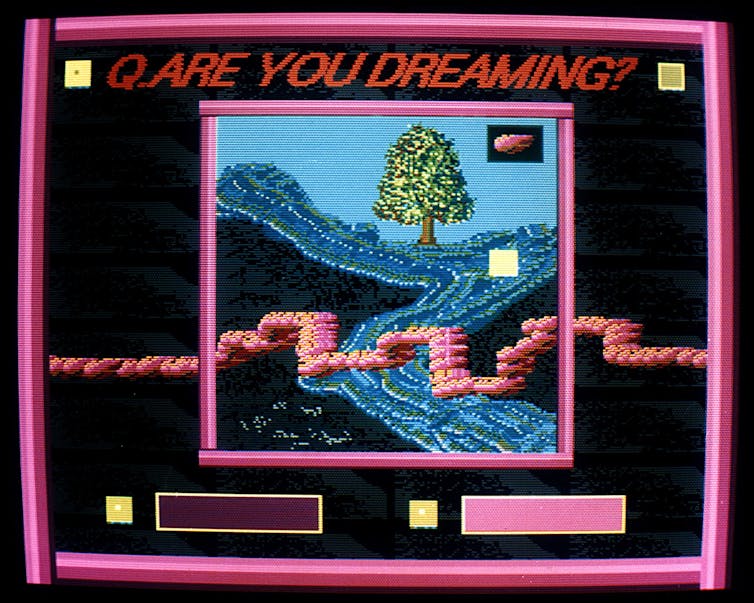

Fictional Videogame Stills/Are You Dreaming? by Suzanne Treister (1991-2) .

Courtesy the artist, Annely Juda Fine Art, London and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

There’s a darker side within the Fictional Videogame Stills of Suzanne Treister, too. Created within the early Nineteen Nineties, they invoke the unconscious desires of the machine by addressing the audience with enigmatic phrases or prompts.

AI runs the danger of erasing history by reworking existing materials and generating its own dreamworlds and hallucinations. This exhibition serves as a reminder that technology itself dreams, and has an unconscious. In short, it has the flexibility to make us conscious of things we’re unaware of – and expand our perception of reality.