In the sweltering summer of AD18, a desperate chant echoed across China’s sun-scorched plains: “Heaven has gone blind!” Thousands of ravenous farmers, their faces smeared with ox blood, marched toward the opulent vaults held by the Han dynasty’s elite rulers.

As recorded in the traditional text Han Shu (the book of Han), these farmers’ calloused hands held bamboo scrolls – ancient “tweets” accusing the bureaucrats of hoarding grain while the farmers’ children gnawed tree bark. The riot’s firebrand warlord leader, Chong Fan, roared: “Drain the paddies!”

Within weeks, the Red Eyebrows, because the protesters became known, had toppled local regimes, raided granaries and – for a fleeting moment – shattered the empire’s rigid hierarchy.

The Han dynasty of China (202BC-AD220) was some of the developed civilisations of its time, alongside the Roman empire. Its development of cheaper and sharper iron ploughs enabled the gathering of unprecedented harvests of grain.

But as an alternative of uplifting the farmers, this technological revolution gave rise to agrarian oligarchs who hired ever-more officials to manipulate their expanding empire. Soon, bureaucrats earned 30 times greater than those tilling the soil.

Windmemories via Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SA

And when droughts struck, the farmers and their families starved while the empire’s elites maintained their opulence. As a famous poem from the following Tang dynasty put it: “While meat and wine go to waste behind vermilion gates, the bones of the frozen dead lie by the roadside.”

Two millennia later, the role of technology in increasing inequality world wide stays a significant political and societal issue. AI-driven “technology panic” – exacerbated by the disruptive efforts of Donald Trump’s recent administration within the US – gives the sensation that all the pieces has been upended. New tech is destroying old certainties; populist revolt is shredding the political consensus.

And yet, as we stand at the sting of this technological cliff, seemingly peering right into a way forward for AI-induced job apocalypses, history whispers: “Calm down. You’ve been here before.”

The link between technology and inequality

Technology is humanity’s cheat code to interrupt free from scarcity. The Han dynasty’s iron plough didn’t just till soil; it doubled crop yields, enriching landlords and swelling tax coffers for emperors while – initially, no less than – leaving peasants further behind. Similarly, Britain’s steam engine didn’t just spin cotton; it built coal barons and factory slums. Today, AI isn’t just automating tasks; it’s creating trillion-dollar tech fiefdoms while destroying myriads of routine jobs.

Technology amplifies productivity by doing more with less. Over centuries, these gains compound, raising economic output and increasing incomes and lifespans. But each innovation reshapes who holds power, who gets wealthy – and who gets left behind.

As the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter warned in the course of the second world war, technological progress is rarely a benign rising tide that lifts all boats. It’s more like a tsunami that drowns some and deposits others on golden shores, amid a process he called “creative destruction”.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

A decade later, Russian-born US economist Simon Kuznets proposed his “inverted-U of inequality”, the Kuznets curve. For many years, this offered a reassuring narrative for residents of democratic nations in search of greater fairness: inequality was an inevitable – but temporary – price of technological progress and the economic growth that comes with it.

In recent years, nonetheless, this evaluation has been sharply questioned. Most notably, French economist Thomas Piketty, in a reappraisal of greater than three centuries of information, argued in 2013 that Kuznets had been misled by historical fluke. The postwar fall in inequality he had observed was not a general law of capitalism, but a product of remarkable events: two world wars, economic depression, and big political reforms.

In normal times, Piketty warned, the forces of capitalism will at all times are inclined to make the wealthy richer, pushing inequality ever higher unless checked by aggressive redistribution.

So, who’s correct? And where does this leave us as we ponder the long run on this latest, AI-driven industrial revolution? In fact, each Kuznets and Piketty were working off quite narrow timeframes in modern human history. Another country, China, offers the prospect to chart patterns of growth and inequality over a for much longer period – attributable to its historical continuity, cultural stability, and ethnic uniformity.

Unlike other ancient civilisations resembling the Egyptians and Mayans, China has maintained a unified identity and unique language for greater than 5,000 years, allowing modern scholars to trace thousand-year-old economic records. So, with colleagues Qiang Wu and Guangyu Tong, I got down to reconcile the ideas of Kuznets and Piketty by studying technological growth and wage inequality in imperial China over 2,000 years – back beyond the birth of Jesus.

To do that, we scoured China’s extraordinarily detailed dynastic archives, including the Book of Han (AD111) and Tang Huiyao (AD961), wherein meticulous scribes recorded the salaries of various rating officials. And here’s what we learned concerning the forces – good and bad, corrupt and selfless – that the majority influenced the rise and fall of inequality in China over the past two millennia.

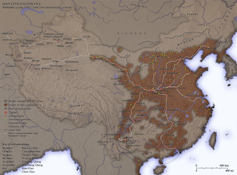

Chinese dynasties and their most influential technologies:

Peng Zhou, CC BY-NC-SA

China’s cycles of growth and inequality

One of the challenges of assessing wage inequality over hundreds of years is that folks were paid various things at different times – resembling grain, silk, silver and even labourers.

The Book of Han records that “a governor’s annual grain salary could fill 20 oxcarts”. Another entry describes how a mid-ranking Han official’s salary included ten servants tasked solely with polishing his ceremonial armour. Ming dynasty officials had their meagre wages supplemented with gifts of silver, while Qing elites hid their wealth in land deals.

Yeu Ninje via Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SA

To enable comparison over two millennia, we invented a “rice standard” – akin to the gold standard that was the idea of the international monetary system for a century from the 1870s. Rice will not be only a staple of Chinese diets, it has been a stable measure of economic life for hundreds of years.

While rice’s dominion began around 7,000BC within the Yangtze river’s fertile marshes, it was not until the Han dynasty that it became the soul of Chinese life. Farmers prayed to the “Divine Farmer” for bountiful harvests, and emperors performed elaborate ploughing rituals to make sure cosmic harmony. A Tang dynasty proverb warned: “No rice within the bowl, bones within the soil.”

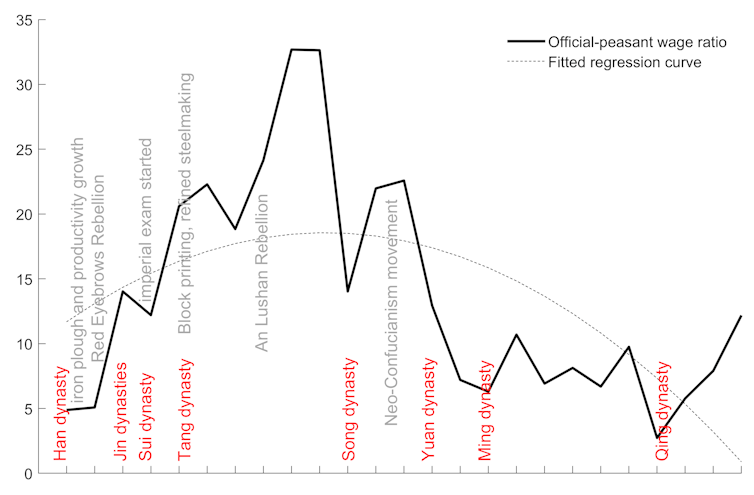

Using price records, we converted every recorded salary – whether paid in silk, silver, rent or servants – into its rice equivalent. We could then compare the “real rice wages” of two categories of individuals we called either “officials” or “peasants” (including farmers), as a way of tracking levels of inequality over the 2 millennia because the start of the Han dynasty in 202BC. This chart shows how real-wage inequality in China rose and fell over the past 2,000 years, in line with our rice-based evaluation.

Official-peasant wage ratio in imperial China over 2,000 years:

Peng Zhou, CC BY-SA

The chart’s black line describes a tug-of-war between growth and inequality over the past two millennia. We found that, across each major dynasty, there have been 4 key aspects driving levels of inequality in China: technology (T), institutions (I), politics (P), and social norms (S). These followed the next cycle with remarkable regularity.

1. Technology triggers an explosion of growth and inequality

During the Han dynasty, recent iron-working techniques led to higher ploughs and irrigation tools. Harvests boomed, enabling the Chinese empire to balloon in each territory and population. But this bounty mostly went to those at the highest of society. Landlords grabbed fields, bureaucrats gained privileges, while strange farmers saw precious little reward. The empire grew richer – but so did the gap between high officials and the peasant majority.

Even when the Han fell around AD220, the rise of wage inequality was barely interrupted. By the time of the Tang dynasty (AD618–907), China was having fun with a golden age. Silk Road trade flourished as two more technological leaps had a profound impact on the country’s fortunes: block printing and refined steelmaking.

Block printing enabled the mass production of books – Buddhist texts, imperial exam guides, poetry anthologies – at unprecedented speed and scale. This helped spread literacy and standardise administration, in addition to sparking a bustling market in bookselling.

Meanwhile, refined steelmaking boosted all the pieces from agricultural tools to weaponry and architectural hardware, lowering costs and raising productivity. With a more literate populace and an abundance of stronger metal goods, China’s economy hit recent heights. Chang’an, then China’s cosmopolitan capital, boasted exotic markets, lavish temples, and a swirl of foreign merchants having fun with the Tang dynasty’s prosperity.

While the Tang dynasty marked the high-water mark for levels of inequality in Chinese history, subsequent dynasties would proceed to wrestle with the identical core dilemma: how do you reap the advantages of growth without allowing an excessively privileged – and increasingly corrupt – bureaucratic class to push everyone else into peril?

2. Institutions slow the rise of inequality

Throughout the 2 millennia, some institutions played a vital role in stabilising the empire after each burst of growth. For example, to alleviate tensions between emperors, officials and peasants, imperial exams referred to as “Ke Ju” were introduced in the course of the Sui dynasty (AD581-618). And by the point of the Song dynasty (AD960-1279) that followed the demise of the Tang, these exams played a dominant role in society.

They addressed high levels of inequality by promoting social mobility: strange civilians were granted greater opportunities to ascend the income ladder by achieving top marks. This induced greater competition amongst officials – and strengthened emperors’ authority over them within the later dynasties. As a result, each the wages of officials and wage inequality went down as their bargaining power steadily diminished.

However, the rise of every recent dynasty was also marked by a growth of bureaucracy that led to inefficiencies, favouritism and bribery. Over time, corrupt practices took root, eroding trust in officialdom and heightening wage inequality as many officials commanded informal fees or outright bribes to sustain their lifestyles.

As a result, while the emergence of certain institutions was capable of put a break on rising inequality, it typically took one other powerful – and sometimes highly destructive – factor to start out reducing it.

The History Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

3. Political infighting and external wars reduce inequality

Eventually, the rampant rise in inequality seen in almost every major Chinese dynasty bred deep tensions – not only between the upper and lower classes, but even between the emperor and their officials.

These pressures were heightened by the pressures of external conflict, as each dynasty waged wars in pursuit of further growth. The Tang’s three century-rule featured conflicts resembling the Eastern Turkic-Tang war (AD626), the Baekje-Goguryeo-Silla war (666), and the Arab-Tang battle of Talas (751).

The resulting demand for more military spending drained imperial coffers, forcing salary cuts for soldiers and tax hikes on the peasants – breeding resentment amongst each that sometimes led to popular uprisings. In a desperate bid for survival, the imperial court then slashed officials’ pay and stripped away their bureaucratic perks.

The result? Inequality plummeted during these times of war and riot – but so did stability. Famine was rife, frontier garrisons mutinied, and for many years, warlords carved out territories while the imperial centre floundered.

So, this shrinking wage gap can’t be said to have resulted in a happier, more stable society. Rather, it reflected the proven fact that everyone – wealthy and poor – was worse off within the chaos. During the ultimate imperial dynasty, the Qing (from the tip of the seventeenth century), real-terms GDP per person was dropping to levels that had last been seen at first of the Han dynasty, 2,000 years earlier.

4. Social norms emphasise harmony, preserve privilege

One other common factor influencing the rise and fall of inequality across China’s dynasties was the shared rules and expectations that developed inside each society.

A striking example is the social norms rooted within the philosophy of Neo-Confucianism, which emerged within the Song dynasty at the tip of the primary millennium – a period sometimes described as China’s version of the Renaissance. It blended the moral philosophy of classical Confucianism – created by the philosopher and political theorist Confucius in the course of the Zhou dynasty (1046-256BC) – with metaphysical elements drawn from each Buddhism and Daoism.

Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

Neo-Confucianism emphasised social harmony, hierarchical order and private virtue – values that reinforced imperial authority and bureaucratic discipline. Unsurprisingly, it quickly gained the support of emperors keen to make sure control of their people, and have become the mainstream school of thought within the Ming and Qing dynasties.

However, Neo-Confucianist considering proved a double-edged sword. Local gentry hijacked this moral authority to fortify their very own power. Clan leaders arrange Confucian schools and performed elaborate ancestral rites, projecting themselves as guardians of tradition.

Over time, these social norms became rigid. What had once fostered order and legitimacy became brittle dogma, more useful for preserving privilege than guiding reform. Neo-Confucian ideals evolved right into a protective veil for entrenched elites. When the burden of crisis eventually got here, they offered little resilience.

The last dynasty

China’s final imperial dynasty, the Qing, collapsed under the burden of multiple uprisings each from inside and without. Despite achieving impressive economic growth in the course of the 18th century – fuelled by agricultural innovation, a population boom, and the roaring global trade in tea and porcelain – levels of inequality exploded, partially attributable to widespread corruption.

The infamous government official Heshen, widely thought to be essentially the most corrupt figure within the Qing dynasty, amassed a private fortune reckoned to exceed the empire’s entire annual revenue (one estimate suggests he amassed 1.1 billion taels of silver, reminiscent of around US$270 billion (£200bn), during his lucrative profession).

Imperial institutions did not restrain the inequality and moral decay that the Qing’s growth had initially masked. The mechanisms that when spurred prosperity – technological advances, centralised bureaucracy and Confucian moral authority – eventually ossified, serving entrenched power quite than adaptive reform.

When shocks like natural disasters and foreign invasions struck, the system could not respond. The collapse of the empire became inevitable – and this time there was no groundbreaking technology to enable a brand new dynasty to take the Qing’s place. Nor were there fresh social ideals or revitalised institutions able to rebooting the imperial model. As foreign powers surged ahead with their very own technological breakthroughs, China’s imperial system collapsed under its own weight. The age of emperors was over.

UtCon Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

The world had turned. As China launched into two centuries of technological and economic stagnation – and political humiliation by the hands of Great Britain and Japan – other nations, led first by Britain after which the US, would step up to construct global empires on the back of latest technological leaps.

In these modern empires, we see the identical 4 key influences on their cycles of growth and inequality – technology, institutions, politics and social norms – but playing out at an ever-faster rate. As the saying goes: history doesn’t repeat itself, but it surely often rhymes.

Rule Britannia

If imperial China’s inequality saga was written in rice and rebellions, Britain’s industrial revolution featured steam and strikes. In Lancashire’s “satanic mills”, steam engines and mechanised looms created industrialists so wealthy that their fortunes dwarfed small nations.

In 1835, social observer Andrew Ure enthused: “Machinery is the grand agent of civilisation.” Yet for a lot of many years, the steam engines, spinning jennies and railways disproportionately enriched the brand new industrial class, just as within the Han dynasty of China 2,000 years earlier. The employees? They inhaled soot, lived in slums – and staged Europe’s first symbolic protest when the Luddites began smashing their looms in 1811.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

During the Nineteenth century, Britain’s richest 1% hoarded as much as 70% of the nation’s wealth, while labourers toiled 16-hour days in mills. In cities like Manchester, child employees earned pennies while industrialists built palaces.

But as inequality peaked in Britain, the backlash brewed. Trade unions formed (and have become legal in 1824) to demand fair wages. Reforms resembling the Factory Acts (1833–1878) banned child labour and capped working hours.

Although government forces intervened to suppress the uprisings, unrest resembling the 1830 Swing Riots and 1842 General Strike exposed deep social and economic inequalities. By 1900, child labour was banned and pensions had been introduced. The 1900 Labour Representation Committee (later the Labour Party) vowed to “promote laws within the direct interests of labour” – a striking echo of how China’s imperial exams had attempted to open paths to power.

Slowly, the working class saw some improvement: real wages for Britain’s poorest employees steadily increased over the latter half of the Nineteenth century, as mass production lowered the price of products and expanding factory employment provided a more stable livelihood than subsistence farming.

And then, two world wars flattened Britain’s elite – the Blitz didn’t discriminate between wealthy and poor neighbourhoods. When peace finally returned, the Beveridge Report gave rise to the welfare state: the NHS, social housing, and pensions.

Income inequality plummeted because of this. The top 1%’s share fell from 70% to fifteen% by 1979. While China’s inequality fell via dynastic collapse, Britain’s decline resulted from war-driven destruction, progressive taxation, and expansive social reforms.

Wealth share of top 1% within the UK

Peng Zhou, CC BY-SA

However, from the Nineteen Eighties onwards, inequality in Britain has begun to rise again. This recent cycle of inequality has coincided with one other technological revolution: the emergence of private computers and knowledge technology — innovations that fundamentally transformed how wealth was created and distributed.

The era was accelerated by deregulation, deindustrialisation and privatisation — policies related to former prime minister Margaret Thatcher, that favoured capital over labour. Trade unions were weakened, income taxes on the very best earners were slashed, and financial markets were unleashed. Today, the richest 1% of UK adults own more 20% of the country’s total wealth.

The UK now appears to be within the worst of each worlds – wrestling with low growth and rising inequality. Yet renewal continues to be nearby. The current UK government’s pledge to streamline regulation and harness AI could spark fresh growth – provided it’s coupled with serious investment in skills, modern infrastructure, and inclusive institutions geared to learn all employees.

At the identical time, history reminds us that technology is a lever, not a panacea. Sustained prosperity comes only when institutional reform and social attitudes evolve in keeping with innovation.

The American century

While China’s growth-and-inequality cycles unfolded over millennia and Britain’s over centuries, America’s story is a fast-forward drama of cycles lasting mere many years. In the early twentieth century, several waves of latest technology widened the gap between wealthy and poor dramatically.

By 1929, because the world teetered on the sting of the Great Depression, John D. Rockefeller had amassed such an enormous fortune – valued at roughly 1.5% of America’s entire GDP – that newspapers hailed him the world’s first billionaire. His wealth stemmed largely from pioneering petroleum and petrochemical ventures including Standard Oil, which dominated oil refining in an age when cars and mechanised transport were exploding in popularity.

Yet this era of unprecedented riches for a handful of magnates coincided with severe imbalances within the broader US economy. The “roaring Twenties” had boosted consumerism and stock speculation, but wage growth for a lot of employees lagged behind skyrocketing corporate profits. By 1929, the highest 1% of Americans owned greater than a 3rd of the nation’s income, making a precariously narrow base of prosperity.

When the US stock market crashed in October 1929, it laid bare how vulnerable the system was to the fortunes of a tiny elite. Millions of on a regular basis Americans – living without adequate savings or safeguards – faced immediate hardship, ushering within the Great Depression. Breadlines snaked through city streets, and banks collapsed under waves of withdrawals they might not meet.

National Archives at College Park via Wikimedia

In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal reshaped American institutions. It introduced unemployment insurance, minimum wages, and public works programmes to support struggling employees, while progressive taxation – with top rates exceeding 90% in the course of the second world war. Roosevelt declared: “The test of our progress will not be whether we add more to the abundance of those that have much – it is whether or not we offer enough for many who have too little.”

In a unique technique to the UK, the second world war proved an excellent leveller for the US – generating hundreds of thousands of jobs and drawing women and minorities into industries they’d long been excluded from. After 1945, the GI Bill expanded education and residential ownership for veterans, helping to construct a strong middle class. Although access remained unequal, especially along racial lines, the era marked a shift toward the norm that prosperity ought to be shared.

Meanwhile, grassroots movements led by figures like Martin Luther King Jr. reshaped social norms about justice. In his lesser-quoted speeches, King warned that “a dream deferred is a dream denied” and launched the Poor People’s Campaign, which demanded jobs, healthcare and housing for all Americans. This narrowing of income distribution in the course of the post-war era was dubbed the “Great Compression” – but it surely didn’t last.

As oil crises of the Seventies marked the tip of the preceding cycle of inequality, one other cycle began with the full-scale emergence of the third industrial revolution, powered by computers, digital networks and knowledge technology.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-ND

As digitalisation transformed business models and labour markets, wealth flowed to those that owned the algorithms, patents and platforms – not those operating the machines. Hi-tech entrepreneurs and Wall Street financiers became the brand new oligarchs. Stock options replaced salaries because the true measure of success, and corporations increasingly rewarded capital over labour.

By the 2000s, the wealth share of the richest 1% climbed to 30% within the US. The gap between the elite minority and dealing majority widened with every company stock market launch, hedge fund bonus and quarterly report tailored to shareholder returns.

But this wasn’t only a market phenomenon – it was institutionally engineered. The Nineteen Eighties ushered within the age of (Ronald) Reaganomics, driven by the conviction that “government will not be the answer to our problem; government the issue”. Following this neoliberalist philosophy, taxes on high incomes were slashed, capital gains were shielded, and labour unions were weakened.

Deregulation gave Wall Street free rein to innovate and speculate, while public investment in housing, healthcare and education was curtailed. The consequences got here to a head in 2008 when the US housing market collapsed and the economic system imploded.

The Global Financial Crisis that followed exposed the fragility of a deregulated economy built on credit bubbles and concentrated risk. Millions of individuals lost their homes and jobs, while banks were rescued with public money. It marked an economic rupture and an ethical reckoning – proof that many years of pro-market policies had produced a system that privatised gain and socialised loss.

Inequality, long growing within the background, now became a glaring, undeniable fault line in American life – and it has remained that way ever since.

Fig 5. Wealth share and income share of top 1% within the US

Peng Zhou, CC BY-SA

So is the US proof that the Kuznets model of inequality is indeed unsuitable? While the chart above shows inequality has flattened within the US because the 2008 financial crisis, there’s little evidence of it actually declining. And within the short term, while Donald Trump’s tariffs are unlikely to do much for growth within the US, his low-tax policies won’t do anything to lift working-class incomes either.

The story of “the American century” is a dizzying sequence of technological revolutions – from transport and manufacturing to the web and now AI – crashing one atop the opposite before institutions, politics or social norms could catch up. In my view, the result will not be a broken cycle but an interrupted one. Like a wheel that never completes its turn, inequality rises, reform stutters – and a brand new wave of disruption begins.

Our unequal AI future?

Like any technological explosion, AI’s potential is dual-edged. Like the Tang dynasty’s bureaucrats hoarding grain, today’s tech giants monopolise data, algorithms and computing power. Management consultant firm McKinsey has predicted that algorithms could automate 30% of jobs by 2030, from lorry drivers to radiologists.

Yet AI also democratises: ChatGPT tutors students in Africa while open-source models resembling DeepSeek empower worldwide startups to challenge Silicon Valley’s oligarchy.

The rise of AI isn’t only a technological revolution – it’s a political battleground. History’s empires collapsed when elites hoarded power; today’s fight over AI mirrors the identical stakes. Will it develop into a tool for collective uplift like Britain’s post-war welfare state? Or a weapon of control akin to Han China’s grain-hoarding bureaucrats?

The answer hinges on who wins these political battles. In Nineteenth-century Britain, factory owners bribed MPs to dam child labour laws. Today, Big Tech spends billions lobbying to neuter AI regulation.

Meanwhile, grassroots movements just like the Algorithmic Justice League demand bans on facial recognition in policing, echoing the Luddites who smashed looms not out of technophobia but to protest exploitation. The query will not be if AI can be regulated but who will write the foundations: corporate lobbyists or citizen coalitions.

The real threat has never been the technology itself, however the concentration of its spoils. When elites hoard tech-driven wealth, social fault-lines crack wide open – as happened greater than 2,000 years ago when the Red Eyebrows marched against Han China’s agricultural monopolies.

To be human is to grow – and to innovate. Technological progress raises inequality faster than incomes, however the response relies on how people band together. Initiatives like “Responsible AI” and “Data for All” reframe digital ethics as a civil right, very similar to Occupy Wall Street exposed wealth gaps. Even memes – like TikTok skits mocking ChatGPT’s biases – shape public sentiment.

There is not any easy path between growth and inequality. But history shows our AI future isn’t preordained in code: it’s written, as at all times, by us.