Digital competence is the flexibility to make use of digital tools and technologies effectively, safely and responsibly. This includes using smartphones and devices, navigating the web and learning the fundamentals of programming.

At a time when digital literacy is more vital than ever, it is crucial to know how young children perceive computer concepts.

As a researcher in computer science education, I led a team of researchers that examined young children's ideas about computers in an African setting. Our current study highlights how children aged five to eight in Nigeria take into consideration computing, including computers, the Internet, coding and artificial intelligence (AI).

While most kids were accustomed to computers and had some understanding of the Internet, programming and AI were largely unknown or misunderstood. Children's understanding was shaped by what they observed at home, at college, and within the media.

This kind of research is very important because early digital literacy prepares children for future learning and careers. In African countries, studies like these underscore the urgent must bridge the digital divide – the wide disparities in access to and exposure to technology. Without early and inclusive computer education, many children risk being left behind in a world where digital skills are essential. They are crucial not just for the roles of tomorrow, but in addition for full participation in society.

The study approach

The study took place in two socioeconomically diverse communities in Ibadan, Nigeria. It provides beneficial insights into the emergence of concepts and concepts related to understanding technology.

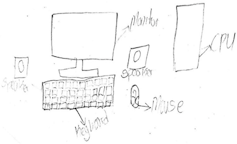

This research chosen a small group of youngsters for an in-depth study slightly than a big sample. Using a “draw and talk” method, the researchers asked 12 children to attract what they thought computers, the Internet, code and AI looked like.

Artificial intelligence implies that machines act intelligently, similar to answering questions or recognizing faces. Coding is writing instructions that tell computers what to do. The Internet is a worldwide network that enables people to attach, share and learn online.

These drawings were followed by interviews to explore the kids's thoughts and experiences. This method revealed not only what the kids knew but in addition how they developed their ideas.

Author provided, Provided by creator (no reuse)

What children know and don't learn about computers

The study found that the majority children were accustomed to computers, often describing them as televisions or typewriters. This comparison illustrates how children relate recent concepts to familiar objects of their environment. However, their understanding was largely limited to what computers looked like. They had little awareness of the inner components or functions beyond “pressing” buttons.

Author provided, Provided by creator (no reuse)

When it got here to the Internet, children's ideas were more abstract. Many people associate the Internet with actions similar to watching videos or sending messages. This was often based on observing their parents using smartphones. Few could say what the Internet actually was or the way it worked. This suggests that children's understanding is formed by observed behaviors slightly than formal instruction.

Provided by creator (no reuse)

Coding and AI were even less understood. Most children had never heard of programming. Those who had offered vague or incorrect definitions, similar to B. the task of “code” to television programs or numbers. AI was also a foreign word for just about all participants. Only two children provided rudimentary explanations based on media presence similar to robots or voice assistants similar to Google.

Provided by creator (no reuse)

Children's misconceptions about computers, coding and AI reflect limited exposure and are consistent across different cultural contexts in Nigeria and outdoors Nigeria. They highlight the necessity for practical programming training and tailored learning models.

This study was based on a previous one study conducted in Finland, and the outcomes also show similarities with others Studies.

The role of language and environment

A key finding of the study is the influence of socioeconomic status and language on children's understanding. Children from the higher-income community generally had more exposure to digital devices and were in a position to express somewhat more informed views, particularly concerning the Internet.

In contrast, children from the lower-income community had limited access. They found it difficult to precise their ideas, especially when computer terms didn’t have equivalents of their native language, Yoruba.

This language barrier highlights a broader challenge in computer science education in Africa. There are few culturally and linguistically appropriate teaching materials. Without localized terminology or relatable examples, children may find it obscure abstract computer concepts.

Implications for education and politics

The study's findings have implications for educators, curriculum developers, and policymakers. First, they emphasize the necessity to introduce computing concepts similar to coding and AI at earlier stages of education.

While many African countries, including Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa, have begun to integrate computers into curricula, the emphasis stays on basic computer skills. There is little emphasis on programming or recent technologies.

Second, research emphasizes the importance of informal learning environments. Children's ideas have been shaped largely through interactions at home and of their communities. It seems that oldsters, guardians and media play a big role in digital early education.

Initiatives like after-school coding clubs, community tech hubs, and parent-focused digital literacy programs could help close this gap.

Finally, the study calls for a more comprehensive and equitable approach to computer science education. Children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds should be given equal opportunities to make use of technology. This includes not only access to devices, but in addition the chance to have meaningful learning experiences that promote curiosity and understanding.

Building a digitally inclusive future

As the digital divide continues to shape educational outcomes worldwide, studies like these offer a roadmap for more inclusive computing education. Educators and policymakers can design interventions which might be developmentally appropriate, culturally relevant, and socially just.

The way forward for computing in Africa depends not only on infrastructure and policy, but in addition on nurturing the curiosity and creativity of the subsequent generation. And that journey begins with listening to how children see the digital world around them.