Anyone who seriously engages in a dialogue with a Large Language Model (LLM) could get the impression that they’re interacting with an intelligence. But many experts in the sphere argue that the impression is just that. In the words of philosopher Daniel Dennett, such systems “showCompetence without understanding“.

The hype surrounding Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) from major corporations and their celebrity spokespeople has led to a backlash during which skepticism turns to cynicism, often with a touch of paranoia about how “Stochastic parrots“can start to regulate our lives.

“Intelligence” itself has change into an overheated topic, requiring less assertiveness, more cool pondering, and recent attempts at a place to begin.

What is intelligence? by Google luminary Blaise Agüera y Arcus is the primary book in a brand new series from MIT in collaboration with Antikytheraa think tank focused on “planetary computation as a philosophical, technological and geopolitical force.” A foreword by series editor Benjamin Bratton makes the daring claim that “computing is a technology that permits you to think” and that the constructing blocks of our reality are themselves computational.

Cmichel67, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Intelligence research has a checkered history marked by eugenics, statistical manipulation and a banal obsession with metrics. Agüera y Arcas counters this by opening up the subject as widely as possible. As a physics graduate with a background in computational neuroscience, he’s something of a polymath. He draws on explanatory frameworks from microbiology, philosophy, linguistics, cybernetics, neuroscience and industrial history.

His book is presented almost as a series of fundamental lectures in these areas. The publication was accompanied by dozens of online lectures and interviews during which Agüera y Arcas argues that we face an enormous shift in the best way we take into consideration intelligence – biological and artificial.

“Few mainstream authors claim that AI is 'real' intelligence,” he writes. “I do.”

Could the nerds be right?

The fundamental argument against “I” in AI is that intelligence is organic and arises from sensory interaction with a physical environment. Agüera y Arcas turns the tables with the premise that computation is the substrate for intelligence in all life forms.

The claim is built on a seemingly crude thesis: prediction is the basic principle of intelligence and “might be the entire story.”

What he means here by prediction is something far more radical than what we see with autocorrect. He explains it in biological terms as a means of pattern development. Individual cells like bacteria predict sequences of events that may influence their ability to survive. The synaptic learning rules in individual neurons result in local sequence prediction.

Agüera y Arcas tells how his journey into the enigmatic terrain of AI reached a turning point when he counterintuitively realized that “the nerds were right”: in computing, larger really was higher, and will actually be the important thing to moving from artificial narrow intelligence (ANI) – the type that may play chess – to artificial general intelligence (AGI) that may engage in a philosophical discussion.

Setting aside his disdain for the seemingly simplistic approach to scaling, Agüera y Arcas returned to the biology laboratory to reassess what might be observed in living systems. If every life form is a set of cooperative parts, he argued, the evolution of cells into organs and organisms might be a matter of predictive modeling.

A central tenet of “What is Intelligence?” is that each life form is a set of cooperative parts. Connections multiply through patterns that enable increasingly complex functions. When Agüera y Arcas says that the brain is computational, it just isn’t a metaphor: brains should not computers, they’re computers.

His deep and abiding interest lies within the connections between biological and mechanical types of intelligence. What is intelligence? follows What is life?a shorter book during which Agüera y Arcas lays the muse for this larger, more ambitious publication.

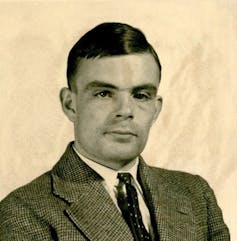

The two questions remain intertwined, if not merged, in his evaluation, which attracts on the basic work of physicists Ewin Schrödingermathematician Alan Turing, John von Neumann And Norbert Weinerand microbiologist Lynn Margulis.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

They are the founders of contemporary fascinated by artificial intelligence, and the seek for its origins runs through all of Agüera y Arcas' research focuses.

It's value noting that Antikythera, the publishing series began by this book, is known as after one old device present in a shipwreck off the coast of Greece and described as the unique analog computer.

The calculation was discovered as much because it was invented, Bratton says in his foreword. This could apply to Antikythera. If it’s indeed the primary computer, it was literally discovered at the underside of an ocean.

But it confirms Bratton's statement in one other sense. As a tool for tracking astronomical phenomena, the Antikythera testifies to computation as a facet of the workings of the universe.

Talk specifically about origins

Agüera y Arcas would really like to enter more detail about its origins. How do patterns emerge from randomness? How does code emerge from a disorganized soup of molecules?

In approaching these questions, he’s guided by Turing and von Neumann, whose experiments anticipated the invention of the molecular structure of DNA in 1953 Turing machine established a minimalist prototype for computing functions with the straightforward components of a coded tape and a read/write head. Von Neumann focused on embodied computation, where the components of the machine or body are a part of the written.

This is where Agüera y Arcas locates his work. His breakthrough got here with the introduction of a programming language developed in 1993 called “BrainfuckUsing just eight command symbols, Brainfuck set the parameters for a controlled experiment during which Agüera y Arcas and his team used 64-byte tapes encoded with “garbage” derived from a soup of code and data.

In the experiment, two tapes are randomly chosen, connected end-to-end, and run to check interaction patterns. Then it's rinse and repeat. The tapes are put back into the soup and two more run.

Amid the randomness, not much will be seen at first. But after about one million repetitions (not huge, mathematically speaking), the magic starts to occur. Loops are created. Patterns emerge. At across the five million mark, the non-functional code or “Turinggas” turns right into a “computorium” for replicating code.

Agüera y Arcas shows a screenshot of this on his laptop in lectures: A vertical line in the course of the info field marks the “phase transition”. The image is featured on the duvet of his book and symbolizes the paradigm shift he’s pursuing.

If the transition to code replication is indeed an expression of what happens in the event of life forms, the idea of natural selection could lose its claim to primacy as an explanatory model for evolution. Richard Dawkins lovers, hold on to your hats.

Agüera y Arcas doesn’t engage in polemical criticism of Dawkins, but his book places Margulis, an early opponent of Dawkins, at the middle of the sector. The pair faced one another in a duel public debate in Oxford in 2009where Dawkins' popular concept of “selfish gene“Come under pressure from Margulis' theory of symbiogenesis, literally creation through combination or fusion.

The Dawkins Report is predicated on a Darwinian view of natural selection through competitive advantage; Margulis drew on research into the formation of microorganisms through mixtures of mitochondria and chloroplasts, once distinct life forms.

It was about survival of the fittest, versus a vision of biological complexity arising through endosymbiosis, a relationship during which one organism lives inside one other, potentially giving rise to a brand new type of life – or, as Agüera y Arcas sees it, a push towards “fit”, understood as pattern completion, reasonably than “fitness”, understood as advantage.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Prediction and performance

Agüera y Arcas' central concepts are prediction and performance, which work together to clarify intelligence as the event of functional complexity through predictive pattern completion.

Here he erases a well known conceptual limit: intelligence doesn’t trigger a function, it really works.

He argues that intelligence is a property of systems reasonably than living things, and performance is its most important indicator. A stone doesn't work, but a kidney does. This is demonstrated by simply halving. The rock becomes two rocks, however the kidney isn’t any longer a kidney.

So does a kidney have intelligence? Or an amoeba? Or a leaf? These questions are raised together with the query of whether large language models are intelligent. This could also be higher phrased than asking in the event that they are intelligent.

Agüera y Arcas just isn’t the just one to take a positive position. Influential biologist Michael Levin leads a research laboratory at Tufts University, where he and his team study the functional connections between natural organisms and artificial or chimeric life forms within the seek for “intelligent behavior in unfamiliar forms.”

Their stated goal is to develop types of communication with truly diverse intelligences, including cells, tissues, organs, synthetic living constructs, robots and software-based AI.

Such an approach steers a course between the stochastic parrot view and biology Rupert SheldrakeThe theory of “morphic resonance” posits that organic form is a manifestation of memory and resonates across generations as a genetic inheritance. Agüera y Arcas avoids each Sheldrake's intuitive and telepathic orientations and the sober constraints of mechanistic determinism.

The ones in What is Intelligence? is more odd than difficult in itself. Many of the reasons are easy to grasp for the overall reader, although Agüera y Arcas tends to delve more into the technical and abstract terrain of programming, as if it were geared toward an insider audience. The extensive glossary doesn’t contain standard programming terms corresponding to: Logic gates, Gradients, Weights And Backpropagation.

On over 600 pages: What is intelligence? is a marathon read and is burdened by tangential excursions. I'm undecided why Agüera y Arcas needs to enter the history of industrialization or anthropological studies of the Pirahā people of the Amazon. This is a book you may immerse yourself in reasonably than devour whole.

But his ideas are necessary. They could well be a part of a serious shift in our fascinated by where human intelligence stands within the rapidly evolving AI environment.